At Home with Chester & Sylvester

An Interview with the Brothers who Brought Back the Catsle

By Stanley O. Smoochie

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This piece is inspired by

’s “At Home With The Actor, Influencer And Designer Philippa Islington-Smythe” and Timothy Ryan’s “Autobiography of a Sri Lankan Cat”.It was a warm afternoon in September when Chester and Sylvester welcomed me into the Catsle. I had not returned since the original location closed a decade previous and I confess that my tail was puffy with nerves. Yet the moment Chester popped his head through the door, my fur settled. His is such a distinctive and ubiquitous face—adorning billboards, magazine covers, and bus stops galore—that upon meeting him I felt as though we were on intimate terms already.

“I get that a lot,” Chester assured me with a slow blink.

He escorted me into the scratching room and introduced me to his brother, Sylvester. Many cats are unaware that the brothers are not biological litter mates, though they both insist that this distinction is irrelevant.

“What does family mean to any cat, let alone a New Yorker?” asked Chester, stretching out on one of several claw-marked couches. “So many of us are born on the streets or in shelters and separated from our litters before we’re even old enough to learn their scents. Sylvester is my brother. End of discussion. That’s why we chose rhyming names.”

I opened my mouth in surprise. Of course it is common for cats to change their names several times over the course of even one of their nine lives, but I had not realized that Chester and Sylvester had done so.

“Fascinating! I always thought the rhyme was a coincidence.”

“No,” said Sylvester (who, as I was coming to realize, is a kitten of few words). “It was strategic. So the other kittens in the shelter would know we had each other’s backs.”

“You make it sound so clinical,” Chester objected with an amused chirp. “We chose each other.”

In the early aughts, the Catsle was a famous New York City institution, passed down through five generations of leadership. Known to felines everywhere as the heart of food, fashion, literature, and bohemian society, the Catsle was first and foremost a haven for unhoused cats seeking respite from overcrowded shelters. Many of its former occupants have gone on to have illustrious careers in the arts. (It is here I must confess, in the spirit of journalistic integrity, that I myself lived in the original Catsle before moving to my current residence.)

Everything changed during the Kitten Crisis. The Catsle’s proprietor at the time, a tuxedo fellow by the name of Smokey, was indicted for tax fraud and fled to Costa Rica. The Catsle had no choice but to close its doors—seemingly for good. Even when the ambitious Egg Roll opened the new location in Astoria, few cats had hope that the Catsle would ever be restored to its former glory.

That is until Chester and Sylvester came scratching at the door.

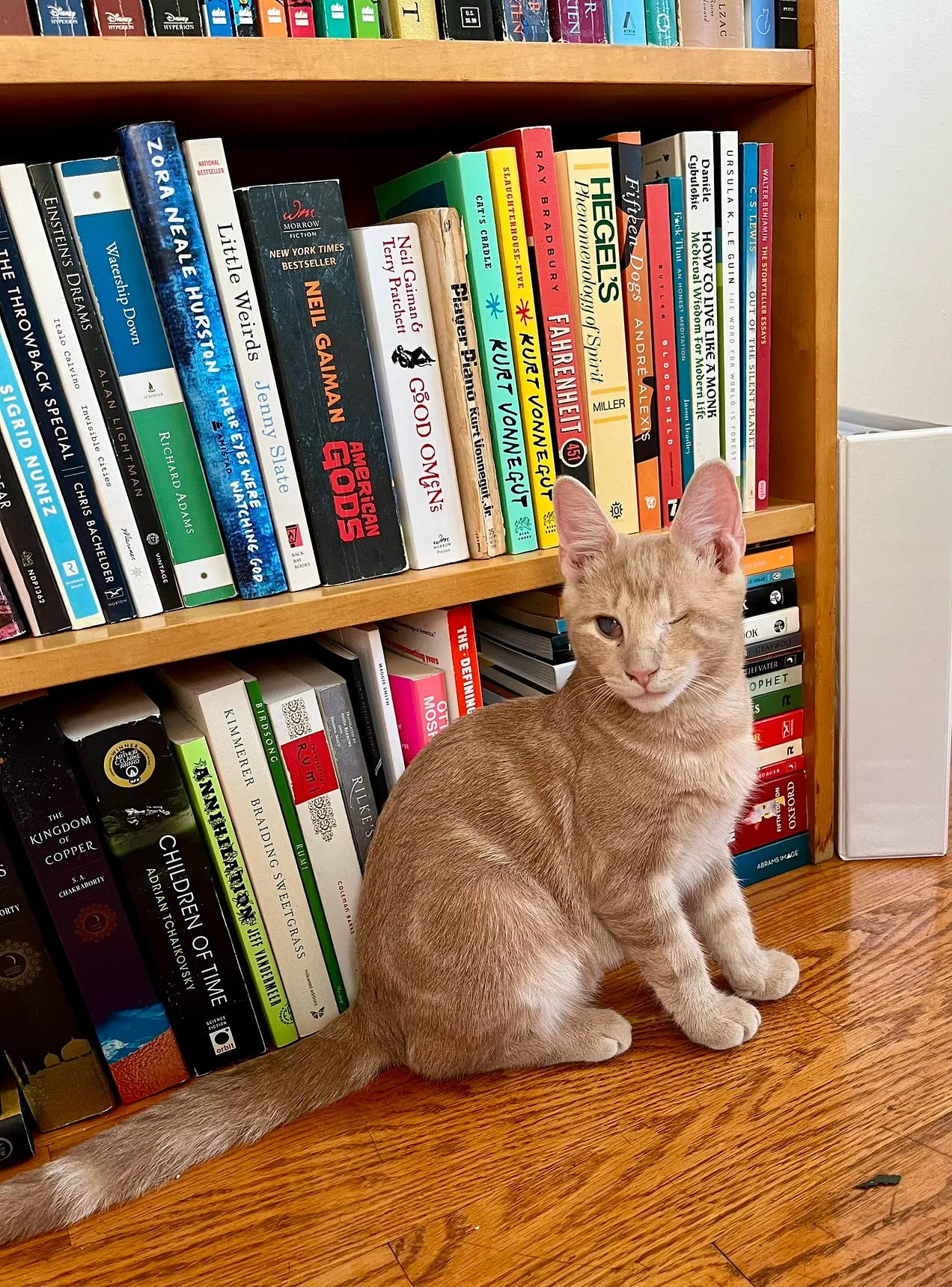

Chester began modeling at only two months old under the stage name Van Winkle—a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgement of the way his face is fixed in a permanent wink. As fans of the preciously precocious kitten know, Chester lost his left eye to infection as an infant and is mostly blind in his right. Yet what some might look at as a tragic obstacle to be overcome, he sees as an interpersonal advantage.

“[The wink] is disarming,” he explained. “It makes cats feel like we’re in on a joke.”

I wholeheartedly agree with this assessment—as did the talent scouts who discovered him at his shelter. His former agent (who could not be reached for comment) famously claimed he was so adorable that she became overwhelmed with emotion and had to excuse herself to hack up a hairball. As she once said to MEOW! Magazine, “That kitten could sell catnip cologne to a mouse.”

But Chester had no interest in selling things. He had set his mind on loftier heights.

Though he could have made an exorbitant living modeling for high-end food and toy brands, Chester chose the philanthropic route, becoming the poster cat for organizations such as FAFA (Fight Against Feline Aids), Catch-&-Release Queens, and the New York Society for Cats with Disabilities—often pro bono.

“I never wanted to be an influencer. Living off sponsorships and selling cats things they don’t need . . . it just feels criminal, especially when there are so many cats who have so little. I want to use my talents—if you can call cuteness a talent—to bring attention to the ways we can care for our community.”

I objected to part of that statement: there is so much more to Chester than “cuteness”—thoughtfulness, warmth, and kindness to name a few—and I simply had to tell him so.

“That’s very nice of you,” he replied graciously. “To tell you the truth, I would have cared about the money if Sylvester had cared. If he had wanted his forever home straight out of the shelter, I would’ve taken a million meaningless gigs to pay for it. But he had connections with Egg Roll through the B.C.B. [Black Cat Bandits] and we both loved the idea of living in the Catsle.”

Here Chester paused, looking wistful. Sylvester said nothing—just continued shredding a cardboard box—but I could tell he was listening intently. It was time, I felt, for the question everyone had been asking.

“There are rumors,” I said, “that you plan to leave the Catsle.”

Chester flicked his ears in acknowledgement. “It’s a wonderful home, but it’s not a forever home. At least, not for us.”

“Will you be leaving together?”

The brothers shared a look. Chester chuckled. “I guess the cat’s out of the bag! No, Sylvester and I are going our separate ways.”

Chester dismissed the speculation that his departure had anything to do with his rumored feud with Egg Roll, insisting that he and the Broadway star remain “the best of friends.”

“My work is calling me to Brooklyn. A certain congressional candidate and I are teaming up on a campaign to increase funds for public health initiatives. I can’t say much more about it at the moment, but keep an eye out in the next election cycle.”

“And what about you?” I asked Sylvester. “What are your plans for the future?”

Sylvester perked up, a feverish glint in his unusual-looking eyes. “You know me. I’ve always got something in the works . . .”

Sylvester is a cat of many names. Known sometimes as Kit Kat, sometimes as Capuchin, and briefly (owing to a misprint in Yarns) as Kombucha, he mainly works under the alias “The Monkey.” Unlike his brother, who thrives in the spotlight, Sylvester operates in the shadows as a street artist, pushing the boundaries of what the public accepts as “art.” His latest and most controversial piece, “THE WORLD IS YOUR LITTER BOX,” involved him urinating in the lobbies of several office buildings on Wall Street. (All of whom asked not to be named in this article.)

“The point is to challenge the cat community’s perception of ‘territory,’” said Sylvester. “Who gets to mark their territory and why? How much territory is enough territory? What does it mean to claim ownership over a location, and is that even ethical in our modern day? The Catsle, for example, belongs to everyone and no one. More places should be like that.”

Sylvester cited Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase “The medium is the message” as his artistic motto. “I prefer working in non-visual mediums. Too often, street art only targets the eyes. What does that mean for cats like Chester? I want my art to incorporate all seven senses.”

The care Sylvester takes to ensure his brother can enjoy his work speaks to the deep compassion behind his art. He is quieter than Chester and certainly more camera-shy, rarely doing any kind of press. But the more time I spent with him, the more I got to know a kitten who keeps his claws sheathed—who is playful, mischievous, and gentle in a subtly radical way.

“My plans aren’t as solidified as Chester’s, but I don’t want that to hold either of us back. We’re not newborns fighting for space in a shelter anymore. We have each other, we have our community, and we have the space to stretch our legs. It’s a big city. I can’t wait to see more of it.”

The Catsle has been home to many iconic duos—Millie and Guan, Domino and Storm, Hoboken NewJersey and Hannah Montana—but perhaps none so beloved as Chester and Sylvester. Toward the end of our time together, Chester pounced on his brother, biting at his ear.

“I’m going to miss you,” he said.

Sylvester shook him off, batting at him playfully. “I’ll miss you, too. But we have nine lives to live. We’ll see each other in the next one.”

Stanley O. Smoochie (he/him) is a Culture writer and photographer for Cats of Queens.

If you like Loose Baggy Monsters, consider leaving a tip! All donations will go toward submission fees for contests and lit mags, helping Jane get her writing out into the world.

and/or