“What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way about.”

—George Orwell

Dear Reader,

This week I cut out two quotes from George Orwell’s essay “Politics and the English Language” and taped them to the desktop I write on. In the first quote, Orwell lays out the six questions he believes every writer should ask themselves when writing a sentence:

“What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? . . . Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?”1

In the second quote, he advises writers to follow six rules:

“(i) Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

(ii) Never use a long word where a short one will do.

(iii) If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

(iv) Never use the passive where you can use the active.

(v) Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

(vi) Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”2

Orwell’s wisdom is keeping me company while I work on line edits for my novel. I’m trying a new technique where I isolate a sentence, copying it and pasting it in its own word document, so that I can hone it without being distracted by the sentences around it. This method has yielded some surprising insights! Sentences that I’ve left unchanged for several drafts suddenly seem insufficient to my more discerning eye.

“Politics and the English Language” primarily targets political writing, so a lot of its advice does not apply to poetry and fiction. However, the way Orwell approaches writing—painstakingly, ensuring that every word is unique, clear, and conveys the meaning he intends—inspired me to do the same.

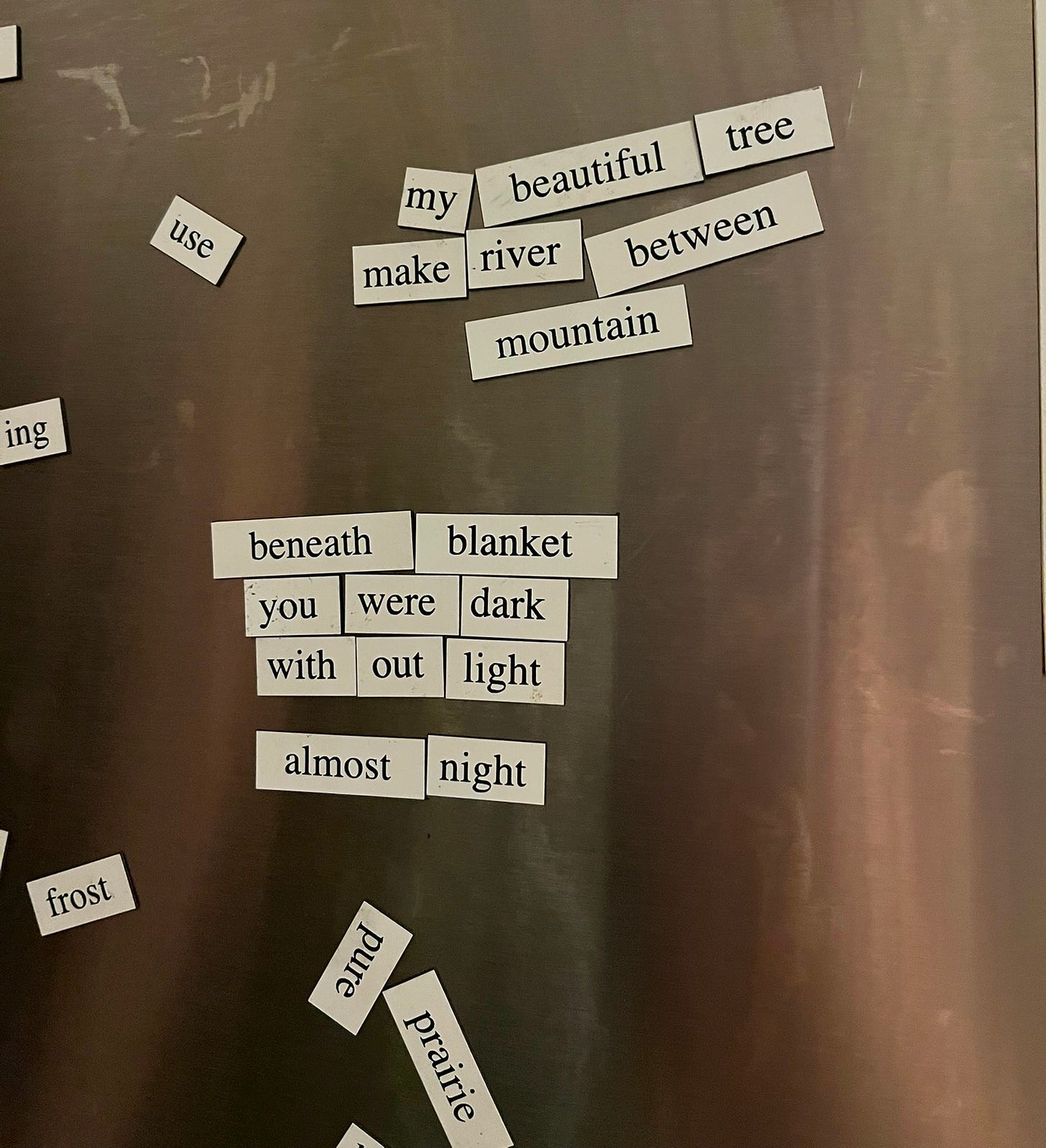

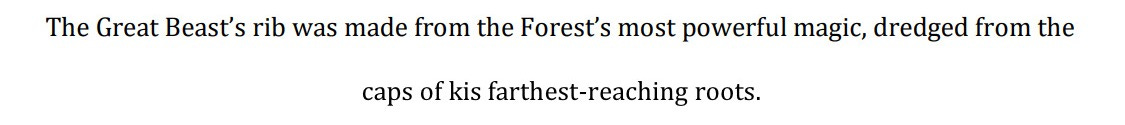

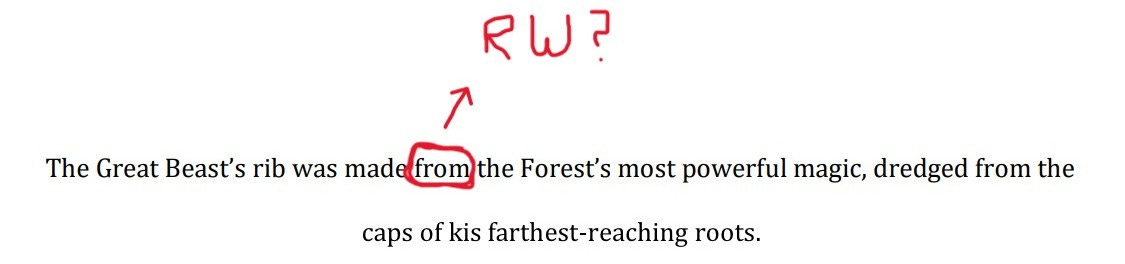

Take this sentence from the first chapter of my novel:

This is a perfectly fine sentence. It does what it needs to do: describes a property of a magical item in the story. Yet, a second look through the lens of Orwell’s questions and rules reveals some places for potential improvement.

Right out of the gate, this sentence breaks Rule (iii) by using the passive voice instead of the active.3 I actually decided to keep it passive for a couple of reasons. First, this sentence and the surrounding paragraph introduce the possessive pronoun “kis” in place of the traditional “its”. I could have written, The Forest made the Great Beast’s rib from kis most powerful magic, but the reader might find that confusing—whose powerful magic is it, the Forest’s or the Great Beast’s?4 Secondly, passive voice is useful for emphasis. In this case, I want to emphasize “the Great Beast’s rib,” so it makes the most sense to make that phrase the subject of the sentence, highlighted at the beginning.

Basically, I have forgone Rule (iii) in favor of Question 6—avoiding saying anything unnecessarily ugly.

Onto the next issue: is “from” the right word here? This goes back to the question, What am I trying to say? What is the difference between “made from” and “made of”? We use the phrase “made from” to describe the process by which something is made, whereas “made of” usually describes a material component. I intended the latter meaning—the rib is made out of the Forest’s magic—so I swapped “from” for “of.”

(I wasn’t entirely happy about this; I liked “from” because of the alliteration with “Forest.” However, this is a novel, not a poem, so it demands different priorities from me.)

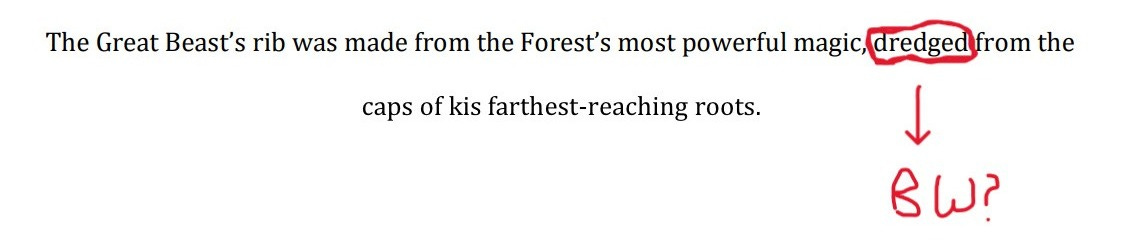

A word’s definition is not the only important consideration; there is also the matter of connotation. According to the OED, to “dredge” means “to collect . . . bring up, fish up, or clear away or out (any object) from the bottom of a river, etc.” Technically this word is correct, but it’s not the best word for the situation. In my mind, “dredging” has a negative connotation; I think of dredging a dead body. So I replaced it with “drawn.” The Forest draws magic from kis roots like water from a well.

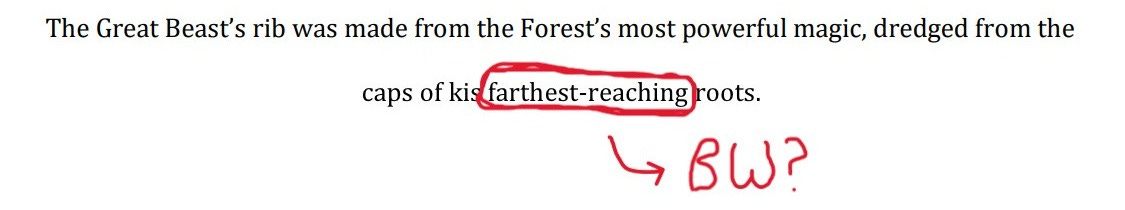

This was definitely an instance where I felt Orwell’s ghost peering over my shoulder with disapproval. “Farthest-reaching” is not a word. (Which is not to say writers can’t make up words from time to time, but in this case I think it’s avoidable.) Once again, my love of alliteration made a fool of me—I enjoy the sound of “reaching roots.” But there’s no need for all those extra syllables. Deepest. Deepest is what I mean.

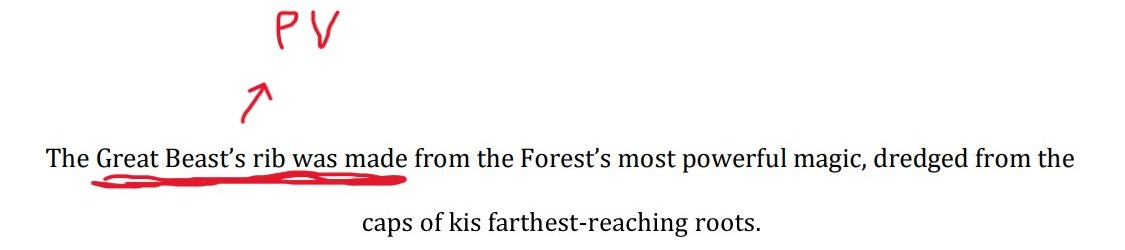

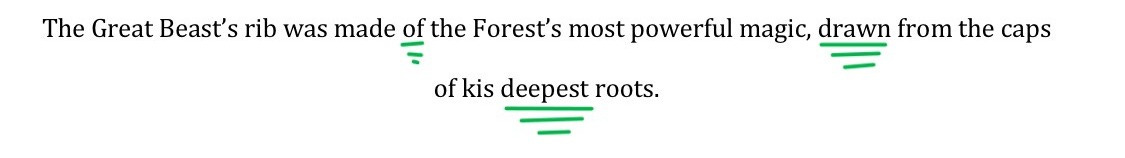

Here is the revised sentence:

The differences are small—so small that I could be accused of being overly fastidious. I very well might be. There’s a good chance I’ll have to revise this novel again in a way that renders my tinkering irrelevant. Every time I think it’s finished, it pulls me back to the beginning again.

Thanks for reading.

Meticulously,

If you like Loose Baggy Monsters, consider leaving a tip! All donations will go toward submission fees for contests and lit mags, helping Jane get her writing into the world.

and/or

George Orwell, “Politics And The English Language,” Horizon 13, no. 76 (1946), 260, accessed via Internet Archive at https://archive.org/details/PoliticsAndTheEnglishLanguage/mode/1up.

Orwell, “Politics And The English Language,” 264.

I learned to identify passive voice using the “by zombies” trick. Take any sentence and insert the words “by zombies” after the verb. If it still makes grammatical sense, the sentence is in passive voice. “The Great Beast’s rib was made [by zombies]” makes grammatical (if not practical) sense; therefore, it is passive.

To read about my use of the pronoun “ki,” check out this post: